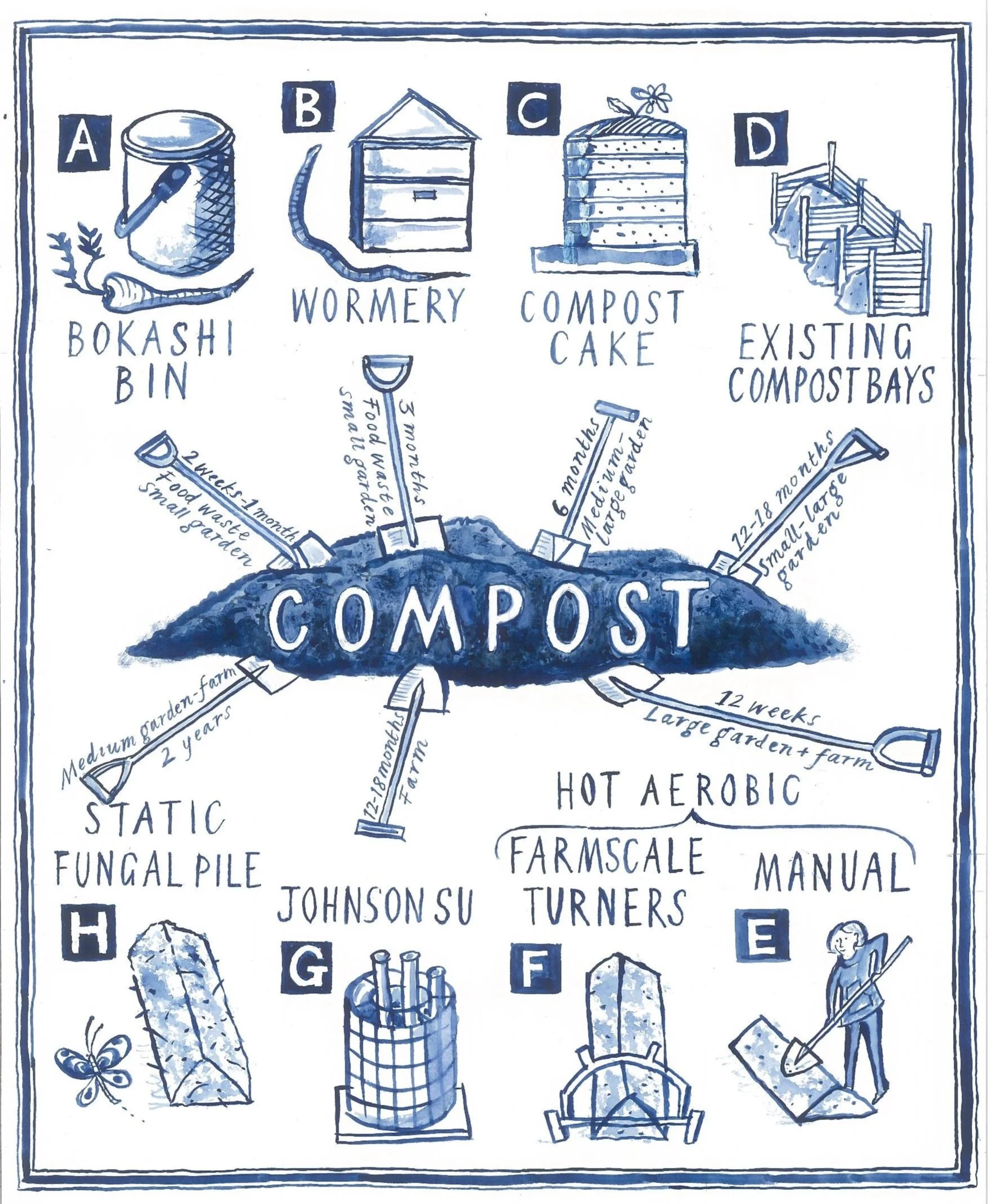

From Bokashi to Johnson-Su, biodynamics to vermicast – compost can be confusing. Cutting through the muck, here's our beginners guide to help find the right method for you.

BOKASHI

EQUIPMENT

A bokashi bucket – a bin with a tight-fitting lid

A bag of inoculated bokashi bran

Kitchen waste

Bokashi is a way of breaking down your kitchen waste through fermentation rather than composting. Unlike aerobic composting it can deal with meat and dairy, and is an anerobic process (i.e. requiring an absence of oxygen) that relies on inoculated bran to ferment the waste. The bran is inoculated with beneficial microbes (or EM - Effective Micro-organisms) that proliferate in anaerobic, acid conditions, similar to the active organisms in yoghurt. You can make the bokashi bran at home (Korean farmers have been collecting and culturing these naturally occurring micro-organisms for centuries) or buy it online.

METHOD

Place your kitchen waste in the bucket, press down and cover with a handful of bran. Repeat each time you add waste.

When the bucket is full, seal it shut and leave it for 2 to 3 weeks to pickle. After 2 to 3 weeks you can bury the Bokashi directly into a fallow spot in your garden as long as it is not near any plant roots. As the Bokashi has fermented the food and neutralised any smells, it should no longer attract vermin when put into your compost.

Alternatively, ‘finish off’ the pickled waste in a wormery (if you have space) or in a Compost Cake. The anaerobic process of the Bokashi bin followed by the aerobic process in the wormery, or your compost, combine to get the most nutrients out of your food waste.

WORMERY

EQUIPMENT

Worm composter – we like a tray wormery

Worm food

Worm bedding

Compost worms (Eisenia fetida - also known as brandling, manure, tiger or red worms).

This type of worm is ideal for converting your kitchen waste into nutrients. Their worm castings, ‘vermicast’, contain a diverse community of microbes which benefit the soil. Unlike earthworms which are soil dwellers, composting worms live in decaying organic matter.

METHOD

Keep your wormery in a shed or sheltered place in your garden (worms like warm, moist conditions). Place a layer of bedding in one tray; compost is perfect. Add the composting worms and cover with food waste, meat, paper, cardboard, tea bags, flowers or leaves.

Avoid dairy, spicy food, grass cuttings and chicken manure. Thereafter add small amounts of waste regularly to feed the worms.

As the worms are surface dwellers they will eat the waste and then move upwards towards the next tray, allowing you to remove the vermicast from the bottom tray. They will survive for up to four weeks without fresh food so you can go on holiday!

TOP TIP: We advise NOT using the liquid which drains off your wormery. As Nicole Masters says ‘This liquid is a combination of the undecomposed food wastes, dribbling through the worm castings. It can contain diseases and nitrates. The production of liquid is telling you that your worm bed is bacterially dominated, and more carbon-rich materials are needed, such as cardboard and wood chips. Good quality commercially available worm tea extracts (vermiliquid) are extracted by flushing water though the finished vermicast. The chocolate colour in vermiliquid is the humic substances and the golden colour is due to fulvic acid – both essential bio-stimulants and plant health promotants.’

BIONDYNAMICS

Biodynamics is a philosophy and an approach to growing. Struck by the damaging route that agriculture was taking, in 1924 Rudolf Steiner launched his Agriculture Course in which he warned against the widespread use of chemical fertilisers, the decline of soil, plant and animal health and the subsequent devitalisation of food. His recommendations formed the basis of the biodynamic method which recognised the interplay of cosmic and earthly influences on the earth.

Jane Scotter grows biodynamically on her farm Fern Verrow in Wales, producing incredible produce for Skye Gyngell’s restaurant Spring in London. As Jane says ‘it gives clarity and understanding of things that are greater than ourselves. It connects you to the unseen forces that work with the polarity of the earth and the planets and the moon. It’s about feel, instinct and intuition’.

We grow biodynamically as often as we can, following the Maria Thun calendar. Observing the lunar effect on plants, Maria divided them into fruit, root, leaf and flowering groups and indicated days for sowing and planting each of them. We also use biodynamic preparations in the garden and compost preparations when we make our Compost Cakes. It seems airy fairy but as Jane say ‘Biodynamics is magic. Not airy fairy silly magic. It is very real’. The more you grow biodynamically the more you feel connected to the seasons, to the rhythms of the earth. And the produce that is grown in this way is undeniably better tasting, healthier and has longer shelf life. You can feel the life force within it.’

BIODYNAMIC PREPARATIONS

There are 9 biodynamic preparations that act like healing remedies for the earth. You can make your own preparations or you can order them through the Biodynamic Association. See Resources for biodynamic books on how to make these preparations and useful websites. We love 500 and 501.

Horn Manure 500: made from cow-manure filled horns buried in September and left in the ground over winter. Spray in the evening or on a cloudy day in spring to bring heat and light forces to pull roots down to give plants a solid foundation.

Horn Silica 501: made from silica-filled horns buried over the summer and stored throughout winter: Spray early on a sunny morning in spring and through the growing season to encourage your plants to stretch upwards like the rising sun and develop their shoots, leaves, flowers and fruits.

COMPOST PREPARATIONS

We use these preparations in our Compost Cakes: Yarrow 502, Chamomile 503, Nettle 504, Oak bark 505 and Dandelion 506 and the liquid Valerian 507.

METHOD

When you have finished your Compost Cake make 5 little balls of clay (you can buy bentonite clay or you may have an area of clay in your garden). Push your finger into one of them and put a pinch of one of the (non-liquid) compost preparations inside it.

Repeat for the other 5 preparations. Place these balls spaced out into 5 holes on the top of your Compost Cake. Pour half the liquid preparation Valerian 507 into a hole in the middle of the cake and then spray the other half over it to mobilise the phosphateactivating bacteria in the pile.

Using Valerian 507: As we allow beautiful, sweet, vanilla-scented valerian flowers to seed freely around the garden, we often make this preparation. Pick the flowers when half open, mix them with water and hang in a bottle from a tree for 3 days. Strain, pour back into the bottle and cork. We use this preparation in spring, spraying it onto plants to protect them against frost and pouring into our Compost Cakes and onto the soil to mobilise phosphate-activating bacteria.

COMPOST BAYS

EQUIPMENT

Ideally 3 or more bays (untreated slatted or solid wood), 1.2m to 1.7m cubed, sitting on soil

Compost or turkey thermometer

Toptex semi-permeable membrane

AS A PANTRY

We use our timber compost bays as a pantry for our Compost Cakes, storing carbon in one bay and nitrogen in another as we gather them until we make our cake. It is important to add layers of fibrous carbon between the nitrogen if we are keeping it for any length of time to stop it putrfiying. For example grass clippings can become a putrified pile of sludge all too quickly so we add layers of autumn leaves, straw, twiggy materials or even cardboard on top of them each time we mow and add them to the pile. We use our third bay for excess turf we have rolled up, clay under a tarpaulin or biochar. When we come to make our Compost Cake all the ingredients are ready and on hand.

TO MAKE COMPOST

Follow the same principles as the Compost Cake to make compost in your existing bays over time.

Start by layering a good depth (30cm) of fibrous carbon at the bottom of the bay and then as you gather greens from your garden or mow the lawn add them to the pile when they are as fresh as possible. These nitrogenous greens fire up the pile but make sure the green layer is no more than 15cm deep otherwise this will become a putrified, anerobic layer.

At this stage, add a layer of carbon such as old hay, leaves, straw, hedge clippings or even cardboard before you add your next layer of nitrogen. We aim for our carbon layer to be two to three times as deep as the layer of nitrogen. To keep the pile moist, water your carbon with a hose as you add it to the pile.

Cover with a layer of toptex to stop it from becoming too wet but still allow it to breathe.

Remember you are trying to ensure there is sufficient temperature, plenty of air and water in the pile. Keep a thermometer in the pile. If the temperature goes over 65 degrees celsius turn it or open up the pile to cool it down.

When the bay is full, turn the pile with a strong fork into a neighbouring timber bay, mixing and watering well and leave for another few months.

When your compost is brown and friable, after approximately 12 to 18 months, it is ready to use in the garden.

JOHNSON-SU BIOREACTOR

A Johnson-Su bioreactor is a method of creating fungal-rich compost developed by molecular biologist Dr Johnson and his wife Hui-Chun Su.

Consisting of a simple barrel of netting filled with dried manure, leaf litter and woodchip with a series of pipes to aid airflow and regular watering, this method produces

microbially rich compost after one year.

STATIC FUNGAL PILE

If you have an abundance of older woodchip you can make it into windrow (Toblerone-shaped pile), water it and then leave it uncovered for 18 months to produce a high-fungal compost. Ideally turn the pile every three months. To learn more about this method see Iain Tolhurst’s website.

HOT AEROBIC COMPOSTING

Hot aerobic composting is a method of producing compost quickly in 8 to 12 weeks. It can either be done manually or with a turner on a farmscale. For those of you happy to make a windrow (Toblerone shaped pile), measure it, and turn it regularly for two weeks, this method is for you.

EQUIPMENT

Compost or turkey thermometer

Inoculum in the form of old compost, Climate Compost or biodynamic preparations

Toptex

Find an area which has a gentle slope in the direction of the length of your windrow to allow rainwater to run off with a stable base (eg. brick, compacted gravel or concrete are best) and protection from the wind.

Start building your windrow (or Toblerone) in layers like a lasagne. You are aiming for a pile 1 to 1.2m high x 1.2m wide and as long as you can manage. We suggest starting with a windrow approximately 2 to 3m long.

Start layering carbon and nitrogen alternately, aiming for a ratio of 3 parts carbon to one part nitrogen.

Innoculate the windrow by adding a bucket of old microbial compost in water or add biodynamic preparations.

Finally add 10% of clay or loamy soil. You can also add layers of seaweed, minerals and bokashi.

Blend the windrow by working along it, turning all the materials in order to mix them up and‘ fluffing’ them with a fork as you go to incorporate air. Keep adding plenty of water as you go. You don’t want it dripping wet, but the heap should always contain about 55 to 60% moisture.

Cover it with a compost fleece such as toptex to protect it from becoming too wet or drying out but allowing it to breathe.

Measure the temperature with a digital thermometer. The windrow must reach 58 degrees celsius for several days (approx. 10 days) in order to kill any pathogens. You may need to add nitrogen if it is not heating up (ideally freshly cut grass clippings).

Turn the pile if it reaches 65 degrees celsius (as beneficial microbial life can only tolerate up to this temperature), adding water as you turn to ensurethe windrow remains moist. You are likely to turn every one to two days during the first week to 10 days, then trailing off as the temperature lowers.

As the windrow cools down there is no need to turn it. When the temperature of the pile reaches ambient temperature and looks and feels fully digested (approximately after 6 to 8 weeks) your compost will be ready to use.